Hello friends,

First of all, a big thank you for signing up to my newsletter. To my surprise, I’ve had quite an emotional couple of days, watching the subscriptions pour in. I don’t know why I’m surprised that so many people want to hear what I have to say – a lot of you have read my books and blogs in the past, after all. Perhaps it’s just the shock of making something public that I have been quietly labouring over for so long.

Anyway, I’m delighted so many of you are reading. When I give talks, the best part of the evening is usually the Q&A at the end, when I actually get to have conversations with people, hear their reactions, and find out which parts of my story have resonated with them. It’s different every time. And I’m hoping the same thing will happen here. One of the things I loved most about blogging was the conversations that went on in the comments. So please don’t be shy about sharing your thoughts below.

This is the first of my monthly round-ups, wherein I’ll be updating you on the places I’ve been, the roads I’ve ridden, the books I’ve read, the people I’ve spoken to, and all the ideas these have given me. (This first one will be a bit longer - there’s some settling-in to do.)

I’ll also give you the heads-up on any public talks I might be giving, link you to any writing I’ve published elsewhere, and make sure you’re aware of all other opportunities to hang out, virtually or in person.

My plan is to send out these round-ups on the first Monday of every month. Paid subscribers will also get a weekly essay, and for founder members I’ll supplement this with a couple of face-to-face chats (or an in-person coffee, if our whereabouts coincide).

Ask Emily

These monthly round-ups will include a section where I answer one reader’s question per month, very much in the style of an agony aunt. I already spend quite a lot of time doing this – people message me asking anything from how to overcome their fear of camping, to what sort of saddle would suit them, to how their cycling event can become more inclusive. So I thought this would be a good way of responding publicly, so multiple people can benefit, and so that I have something to link back to, the next time the question gets asked.

I’ll make it very clear here that I am an expert in some things, and not in others. And furthermore, that a lot of the advice I’ll give is based on my own subjective experience, and might not apply as readily to yours. However, I also have a great many contacts in the cycling world, so if I don’t feel equipped to offer a solution, I will probably be able to speak to people who are.

I’ll start by answering the question that I get asked far more often than any other:

Aren’t you scared, travelling as a solo woman? Would it be safe for me to do the sort of thing that you do?

No, I’m not scared. But I was before I started travelling, and I blame the question itself for this, because it’s all anyone said to me, in the year before I set off on my first big trip. And I’ve thought about it a lot since then, and tried to figure out what evidence people were basing their concerns on. And there isn’t really any – it’s just that people have heard this fear voiced so often that it’s begun to take on the hue of truth. And this makes me quite angry, because how many women have thought about setting off on a solo journey, then been asked this question by every single person they told, and started to think that perhaps it wasn’t such a good idea after all?

I spend a huge amount of time trying to calculate the risks inherent in the things I do, and to separate the actual danger of things happening, from the fear that they will. Fear is an unreliable witness – a distorted mirror through which to view the world. It blurs and confuses, and makes small things seem huge.

Yes, if you spend a bit of time googling, you will find tales of lone female travellers who were attacked, raped and murdered. But aren’t there (sadly) many more incidences of these things happening in our ordinary lives – in the streets, and in our schools, workplaces and homes? And we don’t live in fear of those places, because we have learned to consider them safe.

One of the most high-risk situations a woman can put herself in is living with a male partner. (According to Women’s Aid, a woman is killed by her male partner or former partner every four days in the UK.) And I don’t see anyone asking women if they’re scared when they announce they’re getting married, or moving in with their boyfriend. Perhaps we should start.

The nebulous fears around solo travel also ignore a lot of the nuance of the situation, and the fact that risk can vary enormously from place to place, from person to person, and along countless other axes.

I am a fairly strong-looking white woman, approaching middle-age. Despite the interest my skin colour might provoke in certain regions, it can also act as a deterrent – in a racialised situation, white woman are well known for making a fuss when something goes badly for them, and for being listened to and believed. I cut my hair short a couple of years ago, and I suspect (and hope) that in many places this will reduce the perception of my vulnerability still further. In other places, it might mark me out as queer, in a way that could be problematic. I haven’t yet had the chance to find out. For you, depending on who you are, and how you’re seen, things might be different.

Everyone who travels will have their own unique mixture of ways in which they stand out or blend in, and features that mark them out as a target, or as someone to be helped, befriended or avoided. And what’s more, these will vary considerably from place to place. When I travelled through Pakistan in 2012, I witnessed just how rapidly my status would change – from kidnap risk to honoured guest – as I moved from region to region, and even in some cases from valley to valley. In Indus Kohistan, a local mullah had recently issued a very specific threat against Western women, and I chose to avoid that area. In Lahore and Islamabad, the greatest risk to life was probably, as in most places, the traffic.

There are a handful of regions in the world where a woman with my particular characteristics will be more at risk. But in most places she will be at an advantage. This balance would change if I were – for example – a woman of colour, a trans woman, a refugee, or a woman perceived to have any characteristic that local people feel threatened by, or able to exploit. There are places I’d feel completely safe, where a man of colour, or a visibly queer man, would not. Our unstudied assumptions, that tell us travel is risky, and women are vulnerable, are not really worth very much – the world is an infinitely varied place, and we are infinitely varied people, and the statistics tell us that in almost all cases, provided we have a home, we will make it back there.

I haven’t been able to find recent data for Britons accidentally dying abroad, but when I looked around ten years ago, the top three causes were road collisions, drowning, and falling from balconies. This does not paint a picture of dangerous foreigners, lying in wait to attack us the moment we set foot out of our home country – this looks a lot more to me like people going on holiday and getting drunk (as in this terrifying story about men dying on their stag weekends – perhaps heterosexual marriage is where we should focus our concerns).

It wouldn’t surprise me at all if the robberies and rapes and murders that everyone seems to be so afraid of were geographically concentrated in places like Benidorm and Bangkok. If I were a criminal who planned to target foreigners, I concentrate my efforts there, rather than roaming the Taklamakan Desert or the frozen forests of the Yukon, with the slim hope of finding a defenceless person camping. For one thing, she probably won’t have washed for days.

And something the “aren’t you scared” question misses out, is just how kind most people are, and how much the lone cyclist will be looked after by those she meets, whether she needs it or not. You may not believe this until you actually start travelling – I didn’t. But I have found it to be the case in every single country I’ve cycled through, and when conditions get more challenging (deserts, deep winters, etc.), people become even more attentive. Not only have I never wanted for help or company when I needed it – I have also relaxed into the knowledge that, if something terrible did happen to me (although that’s less likely than it is at home), I would be given the help I need by everyone else.

If you have a question you’d like me to answer, or a knotty problem you want me to address, please drop me a line (no more than three paragraphs, please), and I’ll look forward to coming up with an answer for you next month.

Book recommendation

I read a lot of good books, but whenever anyone asks me to recommend one, I go blank. So a monthly reading round-up will be as useful for me as it is for anyone else.

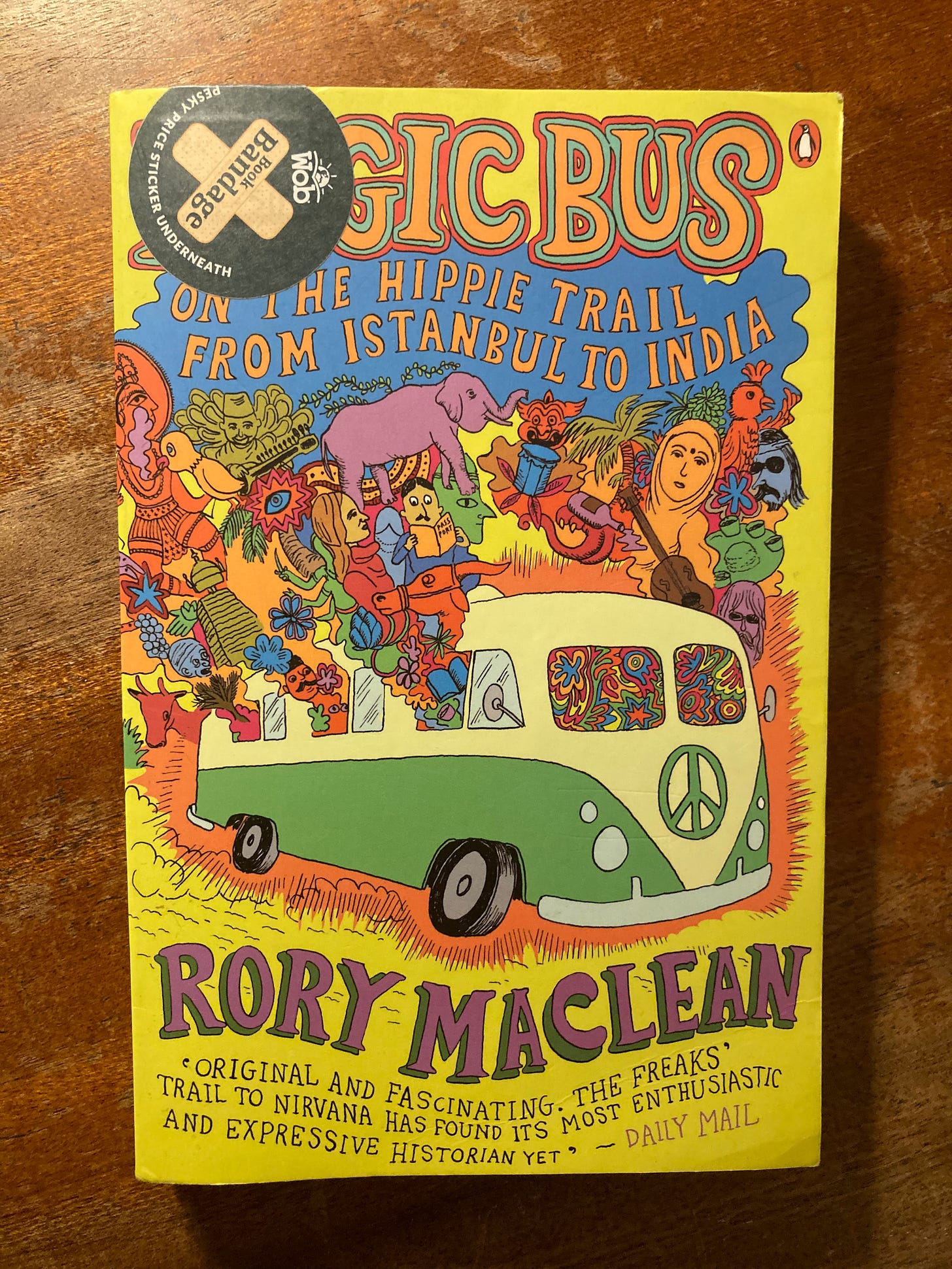

This month I firmly recommend Magic Bus, by Rory MacLean. It’s a travel book, about the author’s journey across Asia in the early 2000s, following the route of the Hippy Trail that existed in the 1960s and 70s.

I loved this book, in part because I love reading about countries I myself have travelled through, both for the joy of revisiting familiar places, and the curiosity of seeing what someone else made of them. But most of my enjoyment came from turning my full gaze on a period of history I had merely glanced at before, and never taken seriously.

I suspect this is not an uncommon thing – hippies are more often portrayed as a bunch of idealistic clowns, than as the powerful social movement they actually were. I grew up in rural Mid Wales in the 1980s and 90s, with parents who had moved there from southern England with a vague notion of raising their children in the sort of rural idyll that the back-to-the-land movement had pursued. In reality, our hippy lifestyle did not extend far beyond vegetarianism and the occasional cheesecloth shirt, but I grew up amidst the gentle social tension between locally-born people, whose families had farmed sheep in the area for as long as anyone could remember, and incomers who ran their smallholdings organically, dyed their hair with henna, cured their ills with reiki, and subscribed to Resurgence magazine.

As a typically conformist child, I strained towards the mainstream preferences of my schoolmates, and did all I could to reject the gaudy trappings of my parents and their friends. As an adult I ended up travelling across Asia myself, though in my case I was alone with a bicycle, rather than passing joints and ideas around the backseats of a long-distance bus. It has only occurred to me since reading Magic Bus that my journey might have been the poorer one.

Not only did the hippies have better company – they were also travelling with the express purpose of being changed by what they encountered. I’m not sure if I’d entirely accept MacLean’s statement that they sought “to be colonised, rather than to colonise”, but reading his book made me realise just how much of the world changed as a result of their journeys, both in the countries they passed through, and in the homelands they returned to.

Until I read this book, my sense of the history of modern overland travel was held up by the two illustrious tent poles of Dervla Murphy and Rory Stewart. She cycled from Ireland to India in 1963; he walked across Asia forty years later. Both wrote books that became foundational to my own ambitions as a traveller. Murphy’s Full Tilt describes Afghanistan as a land of ineffable beauty and friendliness; The Places In Between describes a bleak, broken country, in which the author was not expected to survive. I had dismissed what lay between these two seminal journeys as frivolity, ignoring the huge social and geographical significance of the overland trail. It’s estimated that over two million people travelled across Asia before the Iranian Revolution put a stop to it in 1979. The movement gave birth to a lot of the traditions of modern independent travel, not least the Lonely Planet guidebooks and, for better and for worse, its footprints can still be seen today.

I am constantly thinking about how I can improve the way I travel, both in terms of its value to me as a person, and the impact (or lack thereof) I have on the world as I move through it. And Magic Bus has significantly deepened my understanding of the historical context of one of my longest journeys. Plus, it’s a fantastically entertaining read.

Let me know if you’ve read it, or if you now plan to, or if you know of any similar books that I might enjoy.

*

And a bonus recommendation: during the week when I read Magic Bus, I also happened to listen to a brilliant BBC podcast – Acid Dream: The Great LSD Plot. It’s narrated by Rhys Ifans, it’s a rollicking good story, and it enlightened me as to the fact that 60% of the world’s LSD supply came from Mid Wales, only ten years before my family moved there in the 80s.

Upcoming appearances

I’ve got the following dates in my diary, with more to be announced:

21st March – Rapha Clubhouse, London (a talk on sustainability with Protect Our Winters - more details to come)

3rd May – Reading (details here)

4th May – Winchester (details here)

11th May – Wrexham (details here)

And I’ll be heavily involved in the Edinburgh International Book Festival this year, so if you’re going to be in town for any or all of that, do come and say hi. (More details when they publish the programme.)

That’s it for this month’s round-up! If you subscribe, you’ll also get to read essays on how to abandon your goals, whether you’re eating enough, and how I came up with the name for this newsletter.

Thank you for reading, and for supporting my work,

Emily

Great first (for me) newsletter. I would agree with you about lone travelling. As a lone female, I've come across nothing but kindness from people, once I got over my misgivings and started interacting with them

Great book recommendation, I shall definitely be looking out for it

Completely true about fear of being a lone traveller, what real chance is there of a complete Stranger deciding to attack, rob, rape, murder you. It’s microscopic. What I do on rides and want to stop is to wait just for 10 mins after finding a suitable spot before sleeping and if anyone stumbles by I wait and then move away 10 or 20 more minutes. I use a satellite tracker too so people I trust know where I am.