Dear all,

A few days ago, I was reading a post by one of the many women who are now getting into ultra-distance cycling, and found myself disappointed when she cited Jenny Graham and Lael Wilcox as finally showing that women could do these things too.

I mean no slight to Graham and Wilcox, both of whom I know personally and admire greatly. They’ve achieved magnificent things, inspired thousands of people, and deserve to be even better known than they are. What led me to roll my eyes was this person’s assumption that before these two came on the scene there was no one else – that women completing long bike rides is somehow a new thing.

This is not one person’s fault – it’s something far bigger than that.

Ten years ago, everyone was celebrating Juliana Buhring, who in the space of three years, set a round-the-world record, won the first Transcontinental Race (9th overall), and won the Trans Am Bike Race (4th overall). And Shu Pillinger, the first British woman to complete the Race Across America.

Twelve years before that, Lynne Biddulph set a LEJOG record that stood for 19 years, riding from one end of the UK to the other in 2 days, 4 hours, 45 minutes and 11 seconds – and beating her previous record by over an hour.

Before her, there was Eileen Sheridan, whose 1954 LEJOG1 record stood for 36 years, and Beryl Burton, who is most famous for setting a 12-hour time trial record that briefly surpassed that of the men, but also deserves to be remembered for her seven world titles, and the astonishing fact that she held onto the Best British All-Rounder award for 25 continuous years.2

I’ve cherrypicked these five women from among many more. Some you can learn about in the books I’ve listed at the end; others you’ll need to dig a bit harder for. And it wouldn’t surprise me at all if there are even more whom I haven’t heard of. I often feel a pang of guilt when I discover someone whose achievements ought to be more widely recognised – but as I remarked in one of my essays about Tour de France Femmes last year, how could I have known?

Women have been cycling alongside men ever since cycling existed, and there has always been a small elite cadre who wanted to push boundaries, whatever the boundaries happened to be in their era. But for some reason we forget them as quickly as we can, and hail each female athlete as a pioneer.

So I don’t blame people for assuming that Lael Wilcox and Jenny Graham represent something new, any more than I blame Lael Wilcox and Jenny Graham for being such absolute rockstars. I can’t really blame anyone for this weird collective amnesia, because I don’t think it was ever any one person’s fault or decision – it’s just a puzzling feature of how our culture works, and I am desperate to get to the bottom of it.

The essays I publish here are sometimes a bit different from the sort of articles I might contribute to magazines or anthologies. They’re always as good as I can possibly make them (because you are paying me for this), but a weekly publication schedule, along with all my other professional demands, means that I rarely manage to spend more than two working days on a Substack post.3

Sometimes, as it comes together, I realise that what I’m writing would work better as a longform investigative essay, or a book chapter – or in some cases even a full book, or a PhD thesis. And perhaps eventually I’ll get to return to some of these ideas, follow them to their logical conclusions, and let them take up as much space as they need to. But occasionally I realise I’ll have to publish a piece without having reached the conclusion I was writing towards. One of the advantages of this, of course, is that I then get to hear what my readers have to say on the matter – and quite a few times, a suggestion from the comments has helped me to line my ideas up a bit more closely, or given me something different to chew on. I’m very grateful for this. It’s as if Substack comes with a built-in editorial team.

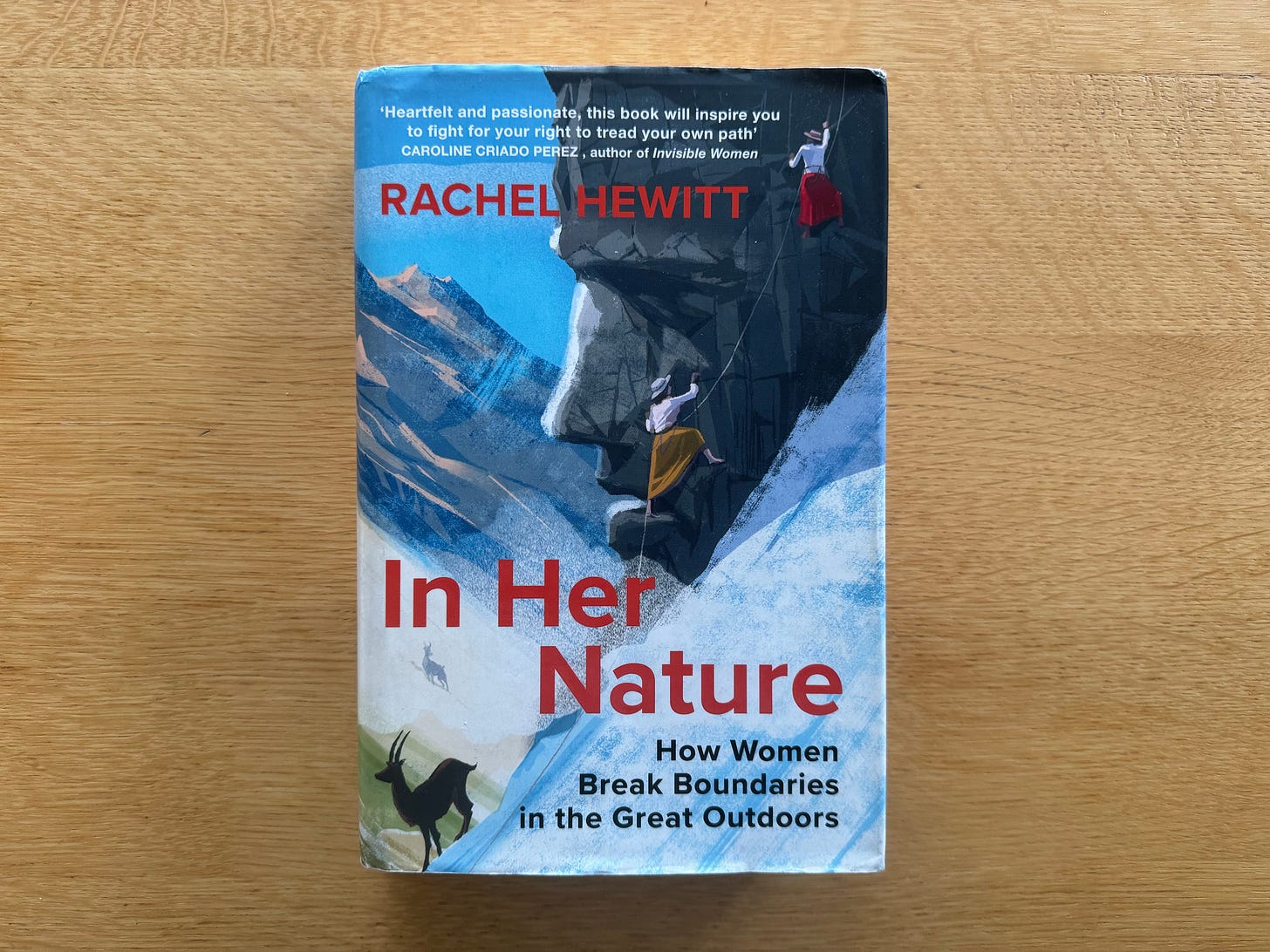

So I don’t think I’m going to come up with a definitive answer for why history persistently forgets women. For one thing, I don’t think there is one, and for another, I think the mechanisms of this forgetting will vary across cultures, societies, and modes of documentation. Rachel Hewitt’s book In Her Nature makes a persuasive case for what happened in mountaineering – very briefly: women participated much more centrally during the heyday of the mid-1800s; then towards the end of the century, an admixture of imperial insecurity and an urge to control the world by documenting it, led to the rise of governing bodies and codified rules and records. These were often controlled by organisations – like universities and the Alpine Club – that excluded women, meaning that not only did women have less opportunity to participate in sport in the first place; their achievements would also be missed, or deliberately ignored even if they did.

It's easy enough to look back at the past and identify how they were getting it wrong. But what I want to do is work out why, after the massive civil rights advances of the twentieth century, and in an era that prizes female empowerment, we not only continue to forget the athletes and explorers of the past, but treat each emerging heroine as though she is the very first to fight her way out of obscurity.

At this stage, it’s beginning to look very much like the obscurity is of our own making. What purpose does it serve? Why are we still hanging onto it?

One of my theories is that it’s simply part of the swarm of unexamined behaviours that constitutes systemic sexism – we have all inherited a lot of this from the generations that came before us, and we’re nowhere near unpicking it yet. For example, I’ve always been at the more woke end of the political spectrum, and I like to think I live my life according to feminist principles – but I still catch myself apologising too much, worrying about my body, undervaluing myself professionally, and (urgh) seeking male approval when I really don’t need to. There’s a lot to unlearn.

On top of all our biases and prejudices, the culture we’re born into hands us a pre-existing web of storytelling conventions, and it’s awfully easy just to fall into them, if you don’t pay attention. If you’ve read Where There’s A Will, you may have noticed that I put the moment where I win the Transcontinental somewhere in the middle of the book, rather than as its grand finale. This was deliberate. I had read enough accounts of long bike rides to know that they almost always ended with a homecoming and a sense of completion, and although this is an obvious and perfectly reasonable way to structure a narrative, it had started to feel samey and predictable. I suspected that bike tourers would have this story in their mind even before they set out on their journey, perhaps with a few choose-your-own-adventure variations (will she meet the love of her life? get kidnapped? run out of money? come to believe in herself?), and that it would bias the way they conducted themselves whilst on the road. They would eagerly look out for episodes, encounters and challenges that supported their pre-conceived narrative arc, and ignore anything that didn’t.4

I think it’s often the same with how we talk about women who travel, adventure, explore and do sport. We’ve got stuck in the narrative of women having to fight their way out of oppression in order to achieve anything, and of their contributions being minimised, discredited and ignored.

It’s not that these things aren’t happening. They very demonstrably are, and have done throughout history. But I’d also argue that we’re now so invested in the woman as underdog – the plucky fighter who overcomes the odds; the hidden figure who gets written out of history – that we don’t do enough to change the script. We want to enjoy the surprise of discovering how much, in fact, women have been up to behind the scenes. We want to savour the outrage of knowing, in comfortable hindsight, how overlooked each emerging heroine has been. We want to amplify her achievements by foregrounding her disadvantages.

But there are other stories available. You could, for example, rewrite history to look at women’s contributions from a different angle. Take the “Victorian lady adventurer.” You can picture her immediately, can’t you? Everyone enjoys the anomaly that these intrepid female explorers and their defiance of convention present – but there are so many of them, and their type is so thoroughly celebrated, that perhaps we need to stop thinking of them as exceptions? Sure, 19th century society was in many ways undeniably conservative and repressive. But given that it gave birth to Isabella Bird, Fanny Bullock Workman, Lizzie Le Blond, Ida Pfeiffer, Gertrude Bell and Hester Stanhope, perhaps we need to take a more nuanced view on the matter. These women were part of their era, just as much as its bathing machines and crinolines.

What you could instead point out about these adventurers is that they all came from wealthy backgrounds. All of a sudden you’re no longer telling a story about women’s oppression – you’re celebrating a lucky few, or you’re noting that a different set of people were debarred from having these adventures, or you’re asking the more difficult questions about why we tend to focus on the exploits of the rich. (After all, people from less wealthy classes also travel, exert themselves and go up mountains, just for different reasons.) Or you could take it from another angle, and look at what all these women (and the men who were adventuring in the same era) went through in their childhoods, to see if there’s a better story there. Or you could mostly ignore the fact that they were women, and examine the significance of their achievements; the contributions they made. I’m not saying that any of these would necessarily be a better, or more accurate way of telling these women’s stories – just that we should reconsider the moulds we wedge our history into.

When I set off to try and cycle round the world in 2011, I don’t think there was really anything standing in my way, except the wrong sort of story. My biggest hurdles were the lack of role models (at least I had Dervla Murphy and Anne Mustoe), and everyone telling me either how dangerous it would be, or how brave I was. I’ve already written a lot about the disservice these conversations do us, and how many women must have been put off travelling as a result of hearing them too often. I very nearly was myself.

And then when I got back I got angry all over again, because I reread Full Tilt, and found several instances where Dervla faces exactly the same warnings that I did. (“You mustn’t ride your bike there. It’ll be dangerous for a lady.”) Didn’t these people realise that she had already proved, half a century before I arrived, that a lady could survive all of this? I’ll admit my annoyance was somewhat irrational, but I think I was disappointed, to find that nothing had really changed, in fifty years.

So, although I’m still not quite sure how, I think we need to update the stories we’re telling. Otherwise we’ll just make the same mistake again and again, and by 2034 we can add Jenny Graham and Lael Wilcox to our list of forgotten heroines.

I’ve got a lot more to say on this matter (maybe someone should write a book about it someday?) but for now I’m going to defer to some people who have done a lot more work than I have on this subject, and offer you not one, but four book recommendations.

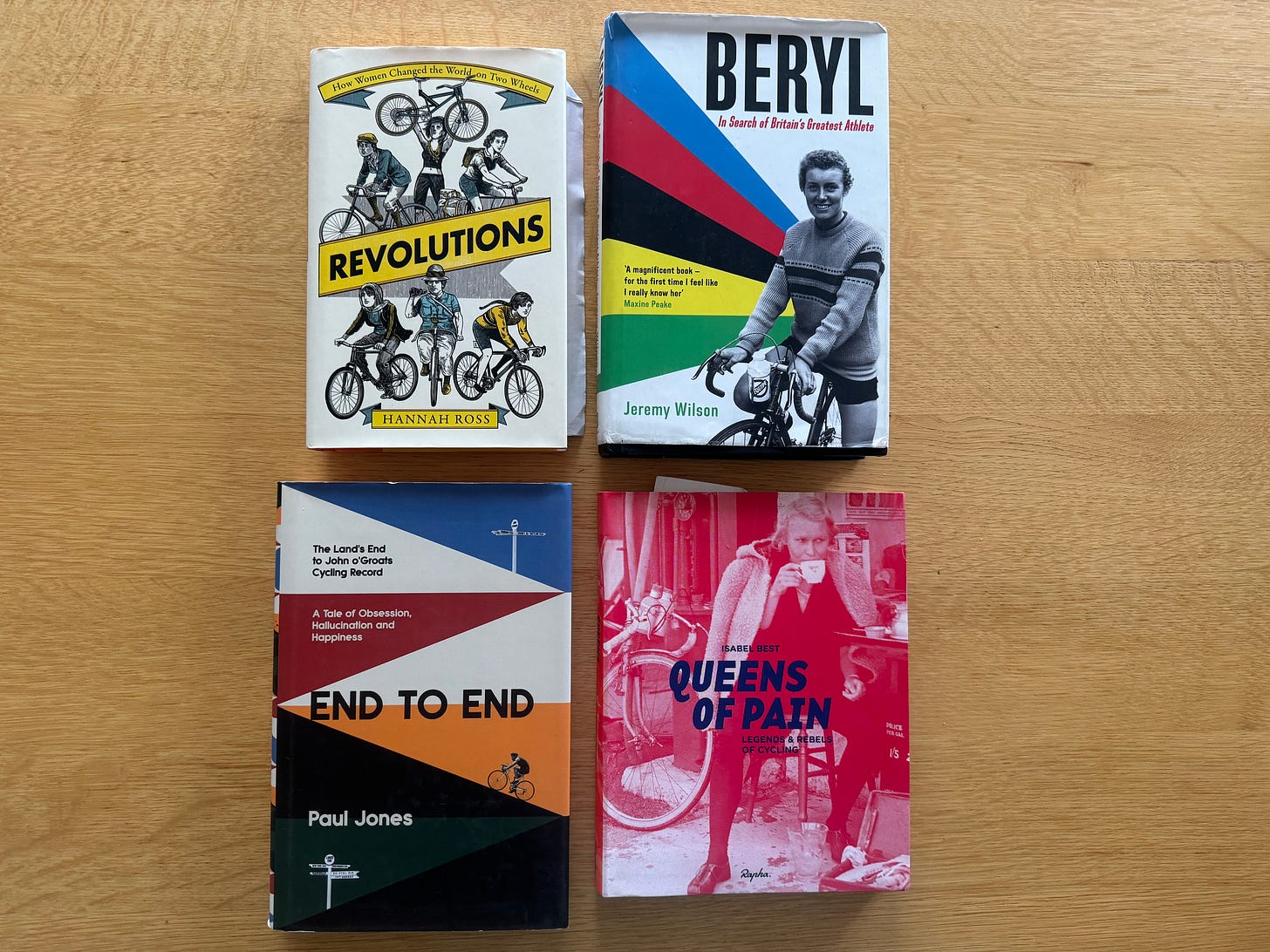

Revolutions, by Hannah Ross

This is effectively a broad (and brilliantly researched) history of women’s cycling. Read it, and you’ll no longer feel any sense of surprise when you hear about a woman doing something impressive on a bike. (Fun fact: Hannah was my publicist when Where There’s A Will came out, so she may indirectly be the reason you’re reading this now.)

Beryl: In Search of Britain’s Greatest Athlete, by Jeremy Wilson

I’ll admit I was almost bored of Beryl when this book came out. Whenever I said anything about women’s cycling on Twitter, some bloke would pop up to tell me yet again about how unfairly forgotten she was. I knew the story of her handing her opponent a liquorice allsort when she overtook him to set her 12-hour time trial record. And I’d already read William Fotheringham’s biography of her, which came out in the same year.

But in spite of all that, I found Jeremy Wilson’s book simply riveting. He breathes new life into the liquorice allsort story, and does a very good job of emphasising (with a certain amount of drama and suspense) just what a big deal it was that Beryl held onto Best All-Rounder for 25 consecutive years. He has clearly spent a lot of time with her surviving family (she died in 1996), and gone to considerable lengths to track down several of the women she used to race against. And he goes to the trouble of setting up an experiment in the wind tunnel at Silverstone, using a rider of Beryl’s exact build, to try and find out what times she would have set today, putting out the same power, but with the advantages of modern kit.

It’s a tour de force. I learned so much more than I thought I’d ever know, about Beryl Burton, and about the world she lived and cycled in.

End To End, by Paul Jones

The premise of this book might seem rather niche - it’s a history of the Land’s End to John O’Groats cycling record - but hear me out. Much like Beryl, it’s full of stories about fascinating people doing incredible things, and what I particularly loved about it is that Paul Jones seems equally interested in women and men, even though they are - for now - competing for different records. You’ll get to read about the magnificent Marguerite Wilson (who set her record in 1939), the effervescent Eileen Sheridan (who set hers in 1954, and died last year, aged 99), and the improbable Pauline Strong (who set hers in 1990, and now lives near Doncaster and works as a truck driver - I want to meet her).

Queens of Pain, by Isabel Best

OK, so you’ve heard of Beryl Burton. You’ve heard of Eileen Sheridan. You might even have heard of Alfonsina Strada, the only woman ever to ride in the Giro d’Italia. But there are so many other female cyclists worth remembering, and Isabel Best documents 26 of them in this beautifully presented, intricately researched book. She reminds us that there has always been much more to women’s cycling than the small handful of female athletes who manage to slip through history’s stranglehold.

We have never been short of heroines. The real question is why we don’t manage to remember them. I’ll make another attempt to answer it in next week’s letter.

Until then,

Emily

Land’s End to John O’Groats.

Everyone loves to point out how uncelebrated BB is – so she’s paradoxically remembered mostly for being forgotten. And she no longer is, really: two biographies have been published in recent years. But she was part of a huge competitive field, and we still don’t hear very much about the women she raced against.

Though some of the more complex ones end up being written in multiple sessions over several weeks, simmering away in the background while I publish pieces that seemed more urgent, or came together more readily.

I definitely started out like this, though my pre-conceived narrative arc ended up bucking and twisting as I went. Now, if I look back more objectively, I see that I’ve abandoned most of my journeys partway through, and with each one I undertook, my sense of home grew hazier, until for a while the road was what I returned to, rather than the hearth.

YES! Emily Chappel! Please write THIS book. Maybe women need more PR - how can we all help…keep talking, keep writing, keep on keeping on

Always have felt similar too, Dervla Murphy is fantastically oblivious to warnings and sensible courses of action and for me is another, if slightly anachronistic, in the model of the Victorian explorer of a certain class. Although, interestingly she is not British which does make her different but also at certain points, more easily accepted; Ireland's neutral and non-colonial recent history prompts a different reaction. Her contacts book certainly helps her along though. Just finished reading Mark Beaumont's account of riding around the world, again some good contacts 'ease' his journey supported remotely by his very determined mother. She for me is the hero of the story, these epic trips often have women at their foundation.

Also think that some of the apparent forgetting of role models and heroes is just a factor of time. Some remain in the memory almost randomly, others not at all. That said, it does tend to be mostly white men still, but things are changing.