Dear all,

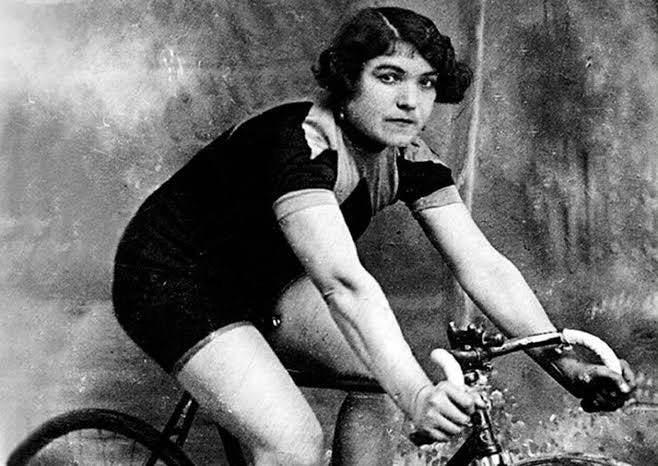

Since last week’s letter, I’ve been continuing to puzzle over why being forgotten (and sometimes ‘rediscovered’) is such a defining biographical feature of female cyclists, explorers and adventurers – and why we seem to be perpetually surprised by every new woman who achieves anything, despite the ample historical precedent set by people like Marguerite Wilson, Kitty Knox, and Alfonsina Strada, to name just a few.

A couple of days ago, an encounter in a theatre in Leeds prompted the realisation that – of course – men get forgotten too. Most of them, in fact. We’ll all fade from memory, eventually, even those who achieve greatness.

But there’s a crucial difference. When the long-ago exploits of some intrepid male cyclist swim back into our consciousness, via a book or a documentary or our own research, no one expresses any surprise that men were up to these things. We assume that they were, even if we can’t recall their names. They had their own Tour de France from the early years of the 20th century, plus it’s generally understood that they undertook expeditions, fought in wars, climbed mountains, and had their own sporting leagues decades – or even centuries – before women did, even if we don’t remember the finer details of who did what.

When this thought struck me, I was sitting in a sold-out auditorium alongside several hundred middle-aged men, and a small handful of women.1 We were there to see Ned Boulting’s Marginal Mystery Tour: 1923 And All That.2 The show is based on Ned’s latest book (about which I’ve now interviewed him several times, so I know it quite well); both tell the story of how he happened to come into possession of two-and-a-half minutes’ worth of footage of stage 4 of the 1923 Tour de France, which had improbably survived on a fragment of Pathé celluloid. Fortuitously (though it won’t have felt so at the time), this coincided with the second lockdown of 2020, so Ned had plenty of time to develop his obsession with this short piece of film, getting to know every frame and every figure, and tumbling down numerous rabbit holes of research as he teased out the warren of stories that lay beneath them.

Among the many discoveries he made (some of them significant, but you’ll have to read the book to find out what they are) was that of Théophile Beeckman, who embarks on a solo breakaway 258km from the stage finish, and who we see riding straight towards the camera at the moment the film abruptly runs out. Boulting speculates it must have burnt on the bulb as it was being projected – and he later finds out that this nitrate film is highly flammable, which probably explains why so few other reports on early Tour stages have survived.

No one had any recollection of Théophile Beeckman before this piece of film came to light in 2020. His achievements had been ignored by cycling historians, there was no monument to him in his hometown in Flanders, and his surviving descendants (who Boulting eventually tracked down) were mostly oblivious to what their ancestor got up to in the 1920s. And yet he was arguably one of the best cyclists of his day. As well as his quixotic breakaway in 1923 (he was caught after 25km, and Albert Dejonghe eventually won the stage), he won a stage in 1924 – and should have worn the yellow jersey, were it not for some creative interpretation of the rules by Henri Desgrange. He won another stage in 1925, but his victory was eclipsed by other events, and thus went under-reported. And he finished the 1926 Tour in fourth place, the closest he ever got to the podium. True, he never attained the superstar status of Henri Pélissier or Ottavio Bottecchia, but if those long-ago Tours de France had played out under modern media scrutiny, he would have definitely have come to our attention.

We only have the bandwidth to remember so many people. Really, not very many at all. If you’d asked me about the great riders of the 1920s before I read Boulting’s book, I could probably have named Pélissier and Bottecchia, but only because I’ve read quite a few other books about the Tour de France, and go through intermittent obsessions with its history. (Plus, both these riders were later murdered, and there’s nothing like a colourful backstory to maintain your historical toehold.) But even I don’t remember that much. One of the best cycling histories I’ve read is Tom Isitt’s Riding In The Zone Rouge,3 and I’m sorry to tell you that, unless I went downstairs, took it off the shelf and had a look, I couldn’t tell you the name of a single one of its protagonists, even though I found their stories captivating when I read it. For the purposes of this article, I just played a little game with myself, where I attempted to list the winners of the men’s Tour de France as far back as I could go. I did better than I thought I would, but was still struck by the fact that some of these names hadn’t crossed my mind for years. And could I tell you about their rivals, or who won the green and polka dot jerseys in those years? No, in many cases, I couldn’t.

At one point during his stage show, Boulting mentioned “the lost generation”, attributing the phrase to Ernest Hemingway. I debated whether to let him know that it was actually coined by Gertrude Stein, but then, flicking through his book to remind myself of Beeckman’s palmares, I found a paragraph on page 117 where he notes that the phrase was “attributed to” Stein, and “popularised by” Hemingway. So the stage show is less accurate on this matter than the book – but I don’t blame him. In a live performance, or a conversation, we have even less space to explain things than we do in a book chapter, and no recourse to footnotes or bibliographies. It would have been fairer to keep the credit with Gertrude Stein, but as Boulting amply demonstrates in his book, pull on any historical thread and you’ll unravel a whole tapestry of stories, authors, facts, theories, arguments and counter-arguments. There simply isn’t space to record them all, so we have to simplify, take the occasional shortcut, shave off a few of each story’s contours, just so that we can keep our audience’s attention.

It's just as important, I realised, to think about why some people are remembered – and how – as it is to question why others are forgotten.

History is written by the winners, as we know – it’s also mostly written about the winners. And although I’ve complained long and hard about this in the past4, on further reflection I can understand why it happens. It’s not just that we’re over-attached to the victory narrative. It’s also that winning takes you to the front of the queue – and the top of the list. Don’t forget that the way we currently write history heavily privileges codification and data. We like the good stories, sure, but we also rely less on them than certain other cultures do, and more on documents and archives and facts and figures. Nothing wrong with this, as such, but it will definitely affect who we give our attention to, and cause us to overlook the women who played football outside of the leagues, the people who cycled a long way for other reasons than to race or set records, and the indigenous mountain dwellers who no doubt often visited certain peaks and altitudes long before any member of the Alpine Club.

That said, having a good story attached to one’s name can cement a winner’s status as a legend, and haul the also-ran out of what Jacky Fleming calls “the dustbin of history.”5 Henri Pélissier is better known for dramatically abandoning the Tour in 1924 than he is for winning it in 1923. Théophile Beeckman will, of course, now be remembered not so much for his modest handful of achievements, but for his unlikely rediscovery by Ned Boulting, and for Boulting’s diligent wringing of every obtainable Beeckman fact from the fabric of history.

I have benefitted from this ‘story bias’ myself. I’m under no illusion that my achievements on the bike, whilst not inconsiderable, would not distinguish me on their own – in pure cycling terms, there are countless people whose talents exceed mine. But for now I’m remembered more than many, because I’ve always written about what I do, in blogs, in books, on social media, and now here. Who knows, perhaps one day in 2124, a researcher will stumble across a copy of Where There’s A Will in a second-hand bookshop or university library, or while sorting through her late grandmother’s effects, and briefly bring my adventures back to life.

So, to stand any decent chance of being remembered by history, you need the success, and you need the story – not only the documented win, but also the tragic death, or the national scandal, or the narrow swerve from obscurity, à la Théophile Beeckman, who will now always be remembered for having previously been forgotten; for the footage of his breakaway to have mysteriously survived, and improbably fallen into the lap of a cycling enthusiast with time on his hands during a global pandemic. How many other breakaways were made, by how many other forgotten riders? How many were missed by the camera, or captured on volatile nitrate film that later combusted, or was thrown away? Loads, I should think. And perhaps those men deserve to be remembered just as much than Beeckman – perhaps we’d enjoy their stories even more. But they didn’t get lucky, and Théo did.

For women, it’s all too often their perceived dance with oblivion that saves them. Beryl Burton, for example, was widely celebrated in her day. The morning after setting her 12-hour record she had to leave Yorkshire at 3am to get down to London for an appearance at the Earl’s Court Cycle Show. That evening she was given a standing ovation by “a packed crowd of cycling fans”6 at Wembley Arena. There’s nothing niche about that. And yet all I ever heard about her for ten years (before the biographies came out), from mansplainers and feminists alike, was that she had been unfairly forgotten. For a while, it was a story more compelling than her success.

I have no doubt that at least a few of the books I recommended in last week’s essay were bought by publishers, and marketed to readers, as ‘untold stories’. We enjoy the sense of discovery when we come across someone whose historical contribution we feel has been unjustly minimised. But ultimately, our capacity to remember them is finite, and our criteria for doing so constricted by bias, boredom, and the brutal consideration of whether a story will ever be useful to us.

So I still don’t have an answer, I’m afraid, though I think I’m now a little closer. It seems there are several ways by which a woman – or anyone – is more likely to endure in history.

You can win something. You can cause a scandal. Or you can be unjustly forgotten, but sufficiently documented that subsequent generations will still be able to find you. If you manage all three, then I think you stand half a chance.

There’s one more element of this that I haven’t quite got my head round yet, and that’s the myth of the exceptional woman. I’ll examine that in a future letter – though perhaps not next week’s, as I think you’ll probably appreciate something lighter after all this.

As ever, I eagerly await your observations in the comments.

Until next week,

Emily

With whom I exchanged expressions of smugness in the toilets during the interval, as we’d all walked straight past a very long queue of men – an enjoyable inversion of the normal state of affairs.

It’s very good, very funny and very clever – go and see it if you can.

The blurb on the publisher’s web page uses words like ‘rediscovered’ and ‘largely forgotten,’ and quoted reviews say things like ‘little known’ and ‘rescued from oblivion’.

Most cycling books can be summarised as “man wins race”, I complained, around the time my second one was published. Although I would heartily recommend one of the honourable exceptions to this rule - Lanterne Rouge, by Max Leonard, which tells the stories of various men who over the years have come last in the Tour de France.

In The Trouble With Women, which I recommend.

A classic (and proof of the theory of forgotten people), though many will not realise this now, is how and when we’ve remembered Alan Turing. Many of us know of him and this ‘story’ now- inventor of the computer, secret war-hero, persecuted by the state, died young by his own hand. Looks like Benedict Cumberbatch…Equally, he also has another forgotten history in biology coining one of our most famous terms (morphogen), and writing a (forgotten then rediscovered) paper on embryonic pattern formation. He has been forgotten, rediscovered but is only partially remembered.